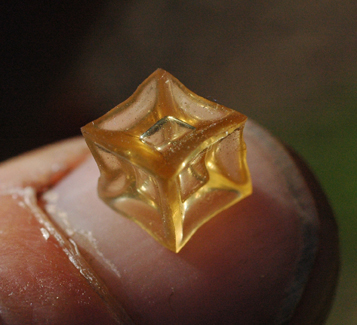

I'm shooting a video series on making high grade hide glue. At least that is the goal, we'll see when I test the glue after it's finished, or maybe have it tested by someone else. The third video, on liming, is uploading to YouTube as I'm typing this. The approach is a sort of learn as you follow along kind of thing, going through the process of turning a cattle hide from Tamara's recent cattle processing class into hide glue. Every time I go to work on the skin, I take some video and edit it down. One section is sort of a lecture type deal with some chalkboard action, one is on fleshing and, aside from the liming one uploading now, the others will be de-hairing and de-liming, cooking and pouring, then finally cutting and drying. Maybe at some point there will be one on testing the finished glue.

This hide glue series will be fairly long, but there are things in there to learn beyond making hide glue. Little snippets about other stuff relating to tanning skins and such inevitably work their way in. No process is an island after all. So far these videos have been decidedly lacking in popularity and the total number of people that really get a lot out of this will probably not be that many. But it will be there when people are ready for it, and that is most of the reason I do this stuff at this point, as a reference archive and so it doesn't all die with me one day. Personally, I think it's really cool, even though I've so far mostly restrained myself from going on long tangents about multiple related processes and ideas. Poking around looking at other hide glue videos on youtube, a lot (or most?) of them use rawhide chew toys cut up in pieces. Nothing wrong with that in context I suppose, but that has never been what we, or the genesis of Paleotechnics, has ever been about. I'm definitely bringing you something closer to the ground up version.

The link below goes to the main Playlist into which all videos in the series will be placed as they come out. I think anyone with any kind of google account, like Gmail, can subscribe for updates. My channel, for now, is a mixed bag of stuff I get up to. I'm also currently also doing a series on amateur apple breeding, which will follow my progress over the years attempting to breed up some new red fleshed apples here at the Turkeysong experimental homestead. For the hide glue series, I'm in the dehairing/refleshing/deliming process now, so that one should be up soon. When finished, I will probably sell the glue on Etsy. If that works, maybe I'll add artisan hide glue making to my list of little income sources. Artisanal hide glue for artisanal artisans, you know instrument makers, fine artists who use traditional materials, fine woodworkers that want their furniture to be fully repairable in the future and the likes of them. People who are keepin' it real! See ya...